Written by William C. Duncan

June 23, 2020

Cache County has recently seen a dramatic increase of COVID-19 cases (from 156 on May 29 to 927 on June 12), many centered around a meatpacking plant in Hyrum. The CDC and state agencies have provided critical backup, but as the Deseret News reported, the increase “was a distress call to churches, nonprofit agencies and volunteers who serve hundreds of refugees and immigrants who live in the Cache Valley, many of whom work in area production and processing plants.”

Throughout the United States, the COVID-19 pandemic has created and made visible significant social needs related to employment, hunger, mental health, and more. Where do we look to meet these needs? The government is part of the answer, but there’s another critical part that often goes overlooked – charitable giving by people of faith. In fact, Sens. Mike Lee, R-Utah, and James Lankford, R-Okla., are sponsoring legislation to increase the non-itemized tax deduction because – as a news report on the bill summarized their position – “Congress needs to encourage more giving to nonprofits because they are more efficient at getting help to local communities than government is.”

Let’s look at government spending, the role of charitable giving in shoring up the safety net, and the unique role of religious giving.

Government spending

National and state governments are making enormous expenditures to assist with these needs, as recent checks many of us have received from the IRS remind us.

The federal government alone has approved $3 trillion for pandemic relief, with $784 billion of that in assistance to individuals in the form of cash assistance, unemployment, etc.

Charitable giving

Government expenditures are well-known and getting lots of attention. But there is another critical source of social support that usually goes unremarked – charitable giving.

Arthur Brooks, former president of the American Enterprise Institute, gives some excellent insights into this sector of our social economy.

First of all, it is significant. Estimates put “the percentage of American households that make monetary contributions each year at 70 to 80 percent, and the average American household contributes more than $1,000 annually.”

Second, it is not primarily motivated by a potential tax break, since “most Americans (particularly middle- and lower-income citizens) don’t even claim the deductions to which they are entitled.”

Third, financial giving is usually coupled with other, informal generosity. Brooks notes a survey that showed “that monetary donors are nearly three times as likely as non-donors to give money informally to friends and strangers.” For example, they are more likely to “donate blood … to give food or money to a homeless person, or to give up their seat to someone on a bus.”

Fourth, charitable giving helps not only with individual needs but may help the economy itself. Research suggests that “$1 given privately would increase GDP by about $15.”

Religious giving

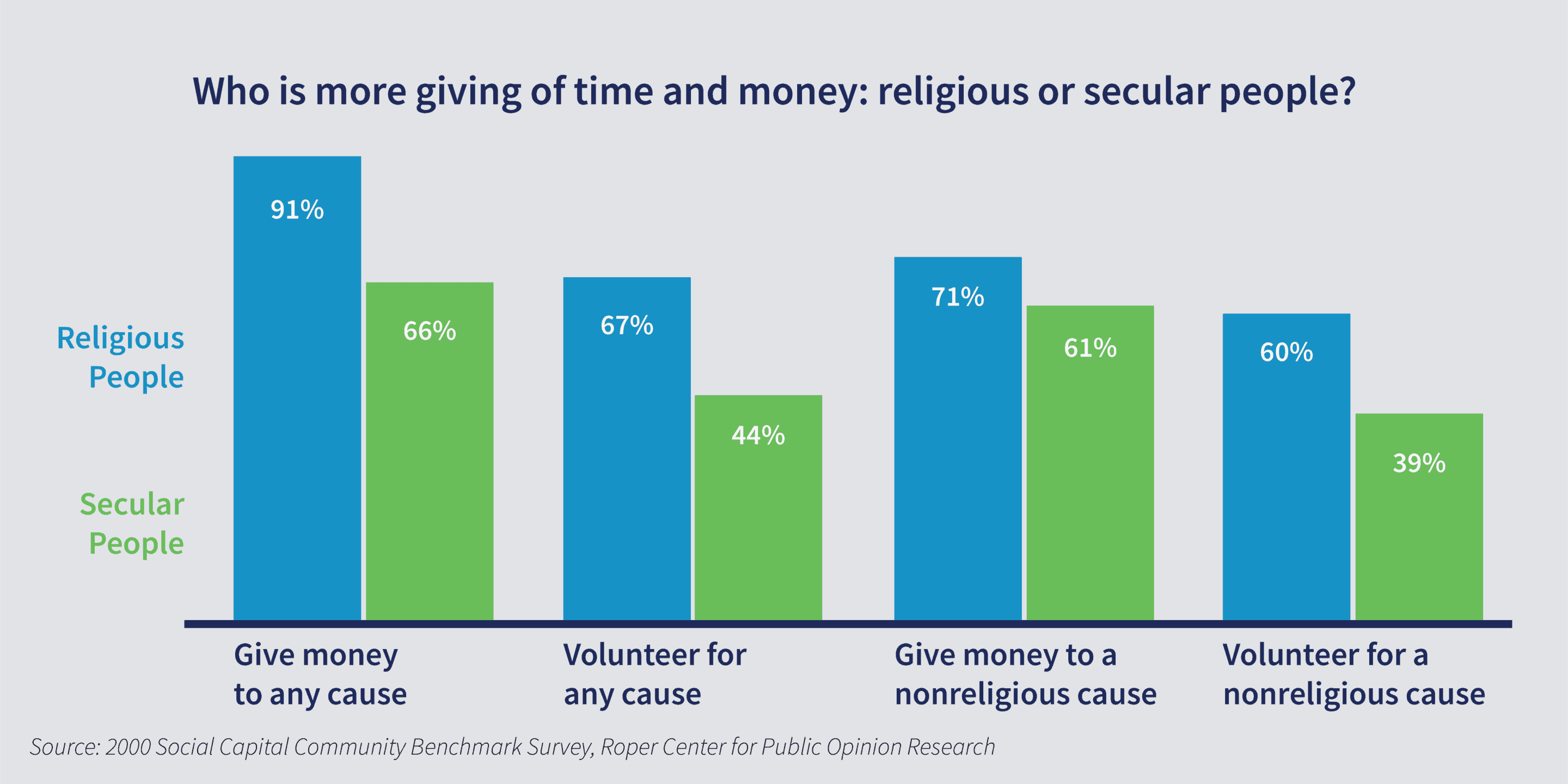

Another insight from Brooks is that religious people are more likely to be generous than those who rarely attend church or don’t affiliate with a religion.

Brooks explains that “religious people gave nearly four times more dollars per year, on average, than secularists ($2,210 versus $642). They also volunteered more than twice as often (12 times per year, versus 5.8 times).” This difference can’t be explained entirely by other differences. Brooks asks us to “imagine two people who are identical in income, education, age, race, and marital status,” but one of them attends church weekly and the other does not attend. “Knowing this, we can predict that the churchgoer will be 21 percentage points more likely to make a charitable gift of money during the year than the nonchurchgoer, and will also be 26 points more likely to volunteer.”

This is not just giving to churches. “The value of the average religious household’s gifts to nonreligious charities was 14 percent higher than that of the average secular household, even after correcting for income differences.”

Charitable giving, particularly religiously motivated giving, will be an important part of pandemic recovery. We don’t have to share faith commitments, or have any religious affiliation at all, to be grateful for that.

As Brooks concludes: “Charitable giving should be seen not just as a nice detail about American life, and even less as a mere tax deduction. It should be seen as a national priority.”

More Insights

Read More

Ignoring the text of the Constitution is a mistake

A written Constitution is entirely superfluous if the document is simply meant to give the people what they want.

What you need to know about election integrity

It should be easy to vote and hard to cheat. This oft-quoted phrase has been articulated as a guiding principle by many elected officials wading into voting and election policy debates in recent years. So why has this issue been so contentious, and what’s the solution?

How transparent are school districts about curriculum?

Utah districts don’t need to wait for legislation to be transparent – many have sought to be transparent on their own. District leaders interested in this reform can do several things right away.