Written by Derek Monson

September 16, 2022

A newly filed lawsuit and a letter from 22 governors to President Joe Biden has kept the president’s federal student loan forgiveness plan in the headlines this week. Biden’s plan aims to use forgiveness of federal student loans through executive action, rather than going through Congress, to boost the economy and help low-income and middle-income families financially harmed by the COVID pandemic.

Opponents of the plan say it will further harm the economy by adding to inflation and argue that Biden lacks authority to broadly forgive student loans without congressional action.

As my Sutherland Institute colleague Nic Dunn recently wrote,

Answering [several key policy] questions can equip citizens to engage in the public debate in a more pragmatic, principled and productive way … asking first whether a policy is legal and constitutional, is well targeted to the right problem, and avoids long-term unintended consequences provides a foundation for healthier and more productive public dialogue.

History offers an additional means to gain understanding of policy issues, like Biden’s loan forgiveness plan, and the dialogue around them.

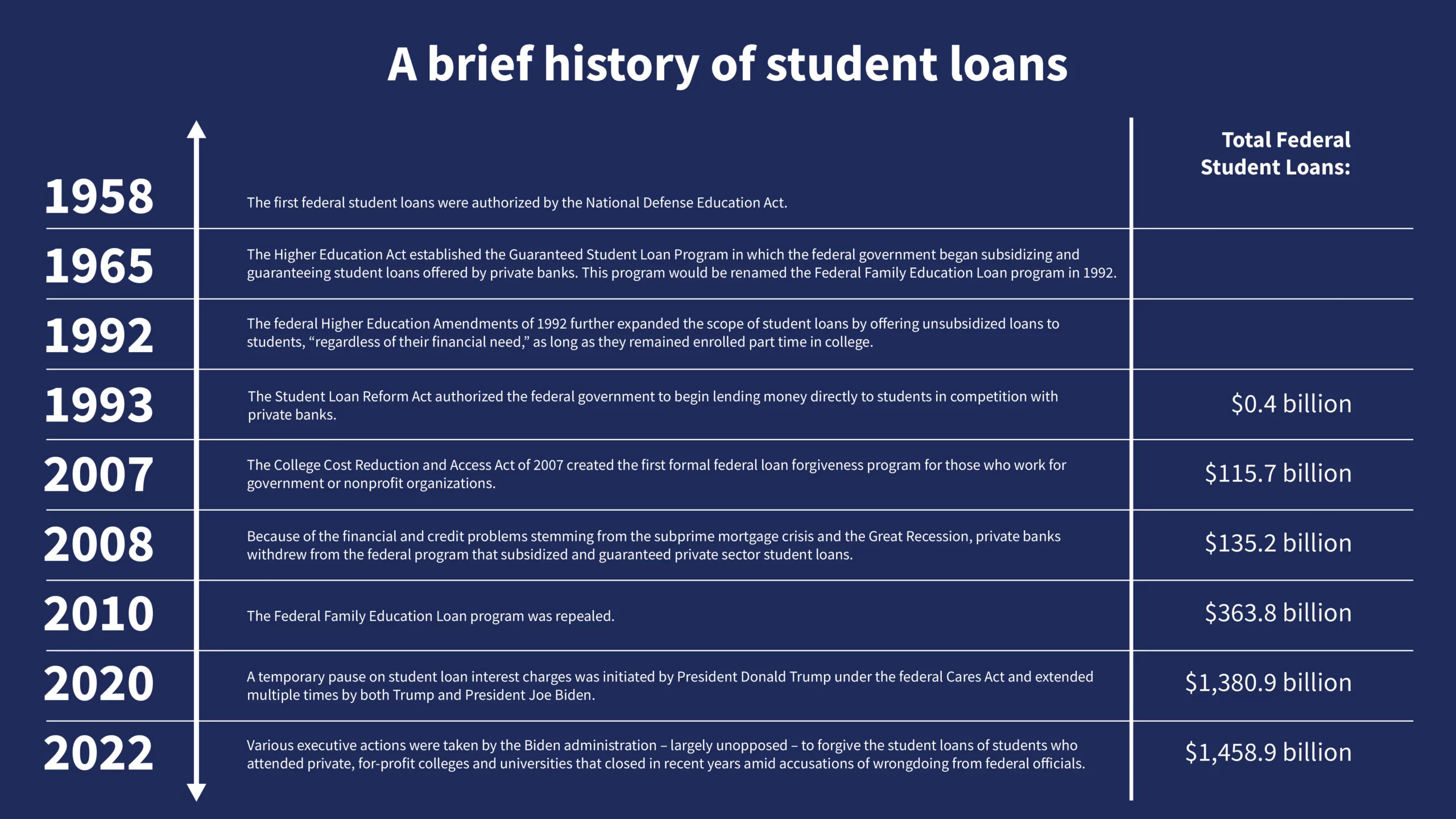

A brief history of student loans

The first federal student loans were authorized in 1958 by the National Defense Education Act as part of a targeted federal program with a clear mission. As part of an effort to compete with the Soviet Union technologically and in defense capacities, the program offered loans “to those majoring in engineering, math, education, science and foreign languages.”

In 1965, the federal government expanded the scope and mission of its student loan programs: They were now aimed at making higher education more accessible for students from low-income and middle-income families. Under the Higher Education Act enacted that year, the federal government created a new student aid program called the Guaranteed Student Loan (GSL) program that began subsidizing and guaranteeing student loans offered by private banks.

The federal Higher Education Amendments of 1992 changed the name of the GSL to the Federal Family Education Loan Program and further expanded the scope of student loans by offering unsubsidized loans to students “regardless of their financial need,” as long as they remained enrolled part time in college. Then in 1993, the Student Loan Reform Act authorized the federal government to begin loaning money directly to students in competition with private banks.

The College Cost Reduction and Access Act of 2007 created the first formal federal loan forgiveness program for those who work for government or nonprofit organizations, known as Public Service Loan Forgiveness. In 2008, because of the financial and credit problems stemming from the subprime mortgage crisis and the Great Recession, private banks withdrew from the Federal Family Education Loan Program, and the program was repealed in 2010. Some banks have continued offering student loans independent of the federal government, but at present the only federally subsidized loans are direct loans from the federal government.

More recent historical events relevant to Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan include: (1) the temporary pause on student loan interest charges initiated in 2020 by President Donald Trump under the federal Cares Act and extended multiple times by both Trump and Biden to the present day, and (2) the various executive actions initiated by the Biden administration – largely unopposed – to forgive the student loans of students who attended private, for-profit colleges and universities that closed in recent years amid accusations of wrongdoing from federal officials.

A brief numerical history of student loans

Between 2004 and 2022 (when adequate data are available), nominal total student loan debt in the U.S. increased from $0.26 trillion to $1.59 trillion – an increase of 511%. During that timeframe, nominal total student loan debt as a percentage of nominal total household debt in the U.S. grew from 3% to 10%.

The nominal median and average individual student loan debt level increased from 2004 to 2022 by 133% and 140%, respectively. By comparison, the nominal average annual cost of tuition and fees at a four-year public university and four-year private university increased during this time by 86% and 76%, respectively.

The total amount of outstanding student loans owed to taxpayers and the federal government saw steady growth between 1993 ($353 million) and 2008 ($135 billion). Total federal student loans then began growing more dramatically – from $135 billion in 2008 to $1.5 trillion in 2022.

Conclusion

It becomes clear from examining the history of student loans that the justifications for Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan had their origins in developments that included the evolution of federal student loan programs: from (1) targeted financial assistance offered through private banks, to (2) expanded financial aid offered through private banks and the federal government, to (3) broad subsidies offered only by the federal government.

In other words, the Biden loan forgiveness plan is attempting a federal government solution to a problem – high levels of student loan debt – that the federal government had a role in creating.

Simply reading the news of the day may fail to illuminate these facts. The historical facts also raise an important question about whether broad student loan forgiveness is a solution to a basic problem or only to a troubling symptom of a deeper problem. In Dunn’s words, “Is the policy well crafted to address the right problem?”

People may look to the history of student loans and arrive at different responses to these questions and issues. But failing to understand the history often means missing some of the important questions and issues entirely – in other words, failing to truly understand the issue.

As the courts are asked to weigh in on the legality of Biden’s plan and as partisan or electoral politics continue to play out around it, we should strive for more than that. We should help encourage policy debate and dialogue, informed by historical facts, that address important policy questions. Through the use of these tools, we can hope to arrive at better policy decisions regardless of which political party benefits or which ideology claims a short-term victory.

More Insights

Read More

Ignoring the text of the Constitution is a mistake

A written Constitution is entirely superfluous if the document is simply meant to give the people what they want.

What you need to know about election integrity

It should be easy to vote and hard to cheat. This oft-quoted phrase has been articulated as a guiding principle by many elected officials wading into voting and election policy debates in recent years. So why has this issue been so contentious, and what’s the solution?

How transparent are school districts about curriculum?

Utah districts don’t need to wait for legislation to be transparent – many have sought to be transparent on their own. District leaders interested in this reform can do several things right away.