Written by Derek Monson

September 15, 2020

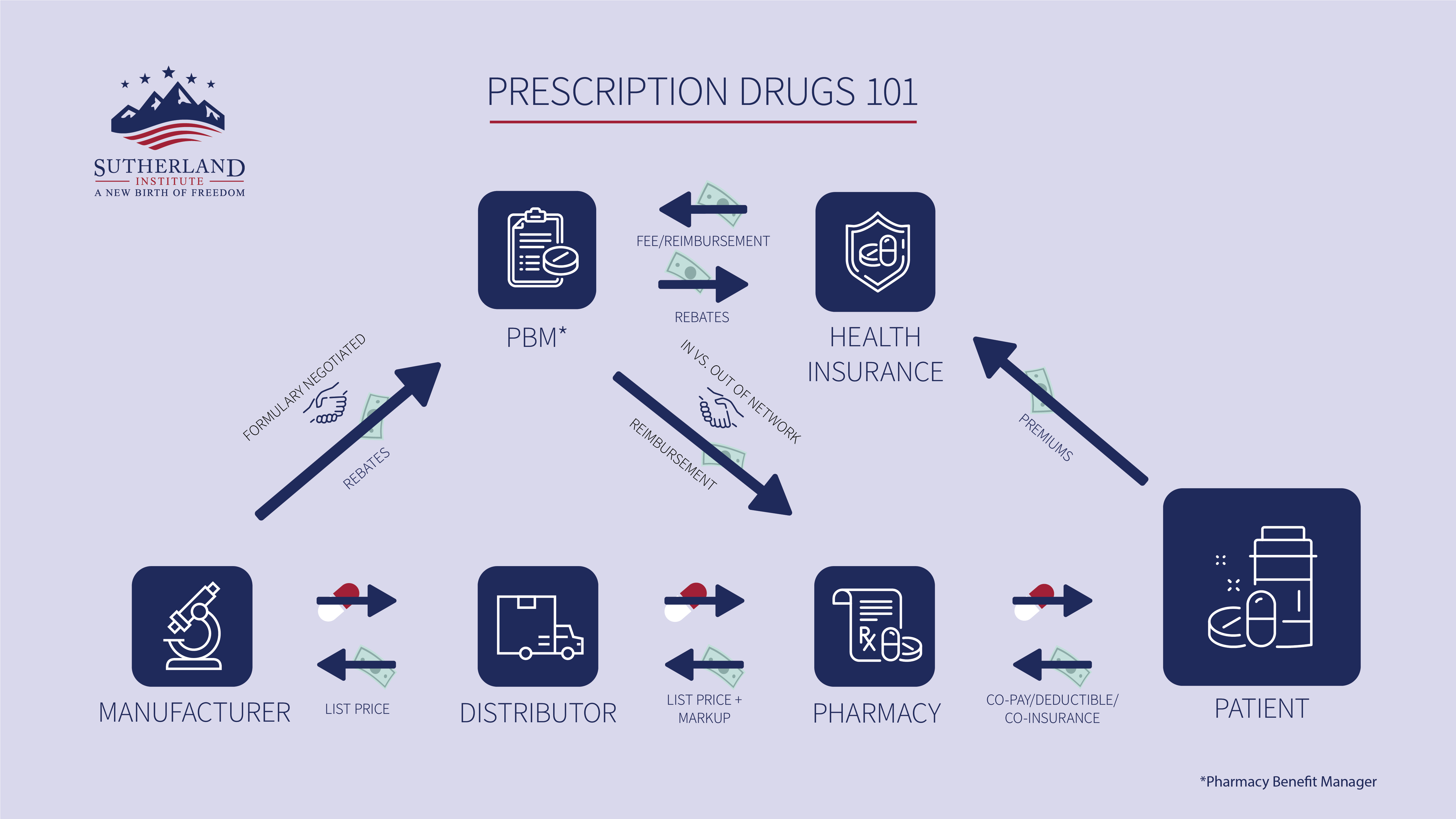

This is part 4 of an ongoing series seeking to describe and decode the prescription drug market for policymakers and the public so we can understand the price we pay at the pharmacy. In previous parts, we introduced the series, offered a review of the players in the prescription drug market, and examined how the money flows. In this part, we will discuss how all of this ultimately determines the price we pay at the pharmacy.

There are six things that ultimately determine how much we pay for a prescription at the pharmacy window:

- Manufacturer’s list price

- PBM-manufacturer negotiations

- Doctors’ recommendations

- Other market players

- Patient choices

- Public policy

Manufacturer’s list price

The list price of a prescription drug (also referred to as wholesale acquisition cost, or WAC) from a manufacturer can influence the price we pay at the pharmacy through health insurance. The amount a pharmacy will charge a patient for a prescription under their prescription drug coverage is determined by the copay (a flat fee the patient pays for every prescription), the deductible (the amount a patient pays before any payment from the health plan), and the coinsurance (the percentage of a drug’s cost that a patient pays after also paying the copay and/or the deductible). In some cases, the drug price a health plan uses to calculate a patient’s coinsurance payment is the manufacturer’s list price. Coinsurance matters because it is a significant and growing portion of the patient’s out-of-pocket costs at the pharmacy.

For example, say a patient named Sarah just got a new health insurance plan with prescription drug coverage at her preferred pharmacy, and the plan includes a $30 copay for each prescription, $200 annual deductible, and then 50 percent of the list price of her medications after meeting her deductible. The list price of one of Sarah’s required monthly prescriptions is $500. When she goes to the pharmacy window to pick up the first month’s prescription, she will have to pay the $30 copay, the $200 deductible and a $250 coinsurance payment (50 percent of the list price of $500), for a total bill of $480.

Now let’s say that the next year, right after Sarah renews her insurance coverage, the drug manufacturer increases the list price of Sarah’s monthly prescription to $600. Her new price in the first month of the year would go up to $530 ($30 co-pay + $200 deductible + $300 co-insurance payment, based on 50 percent of the new list price of $600). So when manufacturers change the list prices of brand-name or generic prescription drugs, it can influence the price we pay at the pharmacy.

PBM-manufacturer negotiation

The PBM negotiates with the manufacturer for rebates on the cost of prescription drugs. Most or all of the rebates get passed onto the health plan. What the PBM has to offer the manufacturer in exchange for higher rebates is placement in a higher tier of a health plan’s formulary, which directly impacts the price patients pay at the pharmacy: A higher-tier placement on the formulary means insurance coverage for the drug is more generous, and the patient pays less for the drug at the pharmacy.

On the other hand, when PBMs seek higher rebates from manufacturers, it reduces the revenues and profits of prescription drug manufacturers. As a result, higher rebates negotiated by PBMs have been connected with increasing list prices from drug manufacturers. Because coinsurance payments for patients at the pharmacy are often based on list prices of prescriptions, higher list prices typically mean higher prices for patients.

Doctors’ recommendations

The prescription that a patient purchases at the pharmacy is highly influenced by what their doctor recommends they take. Some doctors are paid by manufacturers for consulting work, talks and other services. Doctors receiving such payments have been found to prescribe more of that companies’ drugs. Some doctors, on the other hand, generally prescribe generic medications whenever and wherever possible, since they are less expensive for the patient.

For patients, who do not know where particular drugs fall on their plan’s formulary – and thus how much they will have to pay for a particular prescription under their insurance coverage – this means that the doctor’s recommendation on a prescription can indirectly impact how much they pay at the pharmacy.

Other market players

When a doctor prescribes a particular drug to a patient, the patient can use apps like GoodRx to compare prices on that drug at different pharmacies. As a market player, GoodRx acts as something of a virtual marketplace for prescription drug costs that allows a patient to shop around for better prices. GoodRx also negotiates with drug manufacturers to offer discount coupons to patients using its app, to further lower the price patients pay at the pharmacy.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, or ICER, estimates the value of new prescription drugs from manufacturers. Health plans use ICER evaluations to determine how much of a drug’s cost they are willing to cover under their insurance plan. This impacts how much a patient pays for the drug at the pharmacy: More generous coverage means a lower patient price at the pharmacy, and less generous coverage means a higher patient price.

Patient choice

Patient choices impact what they pay at the pharmacy for prescription drugs. They can request a generic version of a prescription, which is typically less expensive than a brand-name drug. They can also pay the cash price for a prescription rather than paying the price determined by their insurance. If the cash price is lower than the insurance co-pay, this can save money for patients.

Alternatively, the patient can choose to purchase different insurance coverage, which will impact their price at the pharmacy if the new health plan’s formulary differs from the old health plan, or if the general parameters of the new health plan’s prescription drug coverage is different than the old plan.

Using Sarah’s purchase of a monthly prescription again as an example, she met her annual deductible with the first month’s drug purchase. This means that after the first month’s price of $480, her monthly price at the pharmacy would drop to $280 (the $30 co-pay plus the $250 co-insurance payment based on 50 percent of the $500 list price). If Sarah chose to get a different insurance plan the following year that had a $150 deductible and co-insurance equal to 30 percent of the drug’s list price (likely meaning a higher monthly premium as well) it would decrease her price at the pharmacy for the first month to $330 and for subsequent months to $180.

Patients can also choose the pharmacy where they purchase their prescriptions, either because they use GoodRx or because a different pharmacy becomes more convenient for them. This choice will impact their prices if their old pharmacy was inside their insurance network and their new pharmacy is outside their insurance network (a status negotiated by the PBM and the pharmacy).

Public Policy

Some federal or state public policies directly impact the price a patient pays for a prescription drug. For instance, Utah lawmakers passed a law that capped copays for insulin prescriptions to diabetic patients at $30 per month. Because this law did not impact list prices for insulin, it will likely result in secondary financial impacts on patients as well (e.g., higher insurance premiums).

At the federal level, a 2018 law banned “gag orders” in contracts between PBMs and pharmacies. These “gag orders” prevented pharmacists from letting patients know if a cash price for a prescription was lower than the price the patient would pay under their insurance coverage.

These are just a few examples of how public policy can significantly impact the price we pay at the pharmacy.

Conclusion

Of the many factors that influence the price we pay at the pharmacy, only a few are controlled by the patient. Some factors can be influenced by policymakers – whom patients elect – but the complexity of the prescription drug market is critically important for such policy considerations. There are often unintended secondary or tertiary impacts from potential policy reform. If we better understand how the market determines the price we pay at the pharmacy, we can help improve public policy – and prescription drugs can become more affordable for all.

More Insights

Read More

What you need to know about the upcoming state party conventions

The two major political parties are about to hold their state conventions. Here’s what you need to know.

Here’s why the First Amendment’s religion clauses are not in conflict

Some suggest there is a tension between protection for the free exercise of religion and the prohibition on the establishment of religion. But a better take is to see the two clauses as congruent.

Is California’s minimum wage hike a mistake?

Is raising the minimum wage a good tool to help low-income workers achieve upward mobility? That’s the key question at the heart of the debate over California’s new $20 an hour minimum wage law for fast food workers.