Written by Nic Dunn

December 2, 2022

Originally published by Deseret News.

When she got married and started a family, Abby Shaha already had close to a decade of professional experience in communications and public relations, which meant she faced a crossroads.

“I felt like I had this choice: Well, you can work, or you can be at home,” the Utah mom told me. She saw both her career and her new role as a mother as important parts of her future but she didn’t initially see many options for blending the two roles.

“I wanted to be more present in my kids’ lives than the traditional office hours were going to let me,” she said.

Shaha’s dilemma illustrates a trend that has grown since the start of the pandemic: Parents want more freedom to arrange work and family life in a way that prioritizes time with their children.

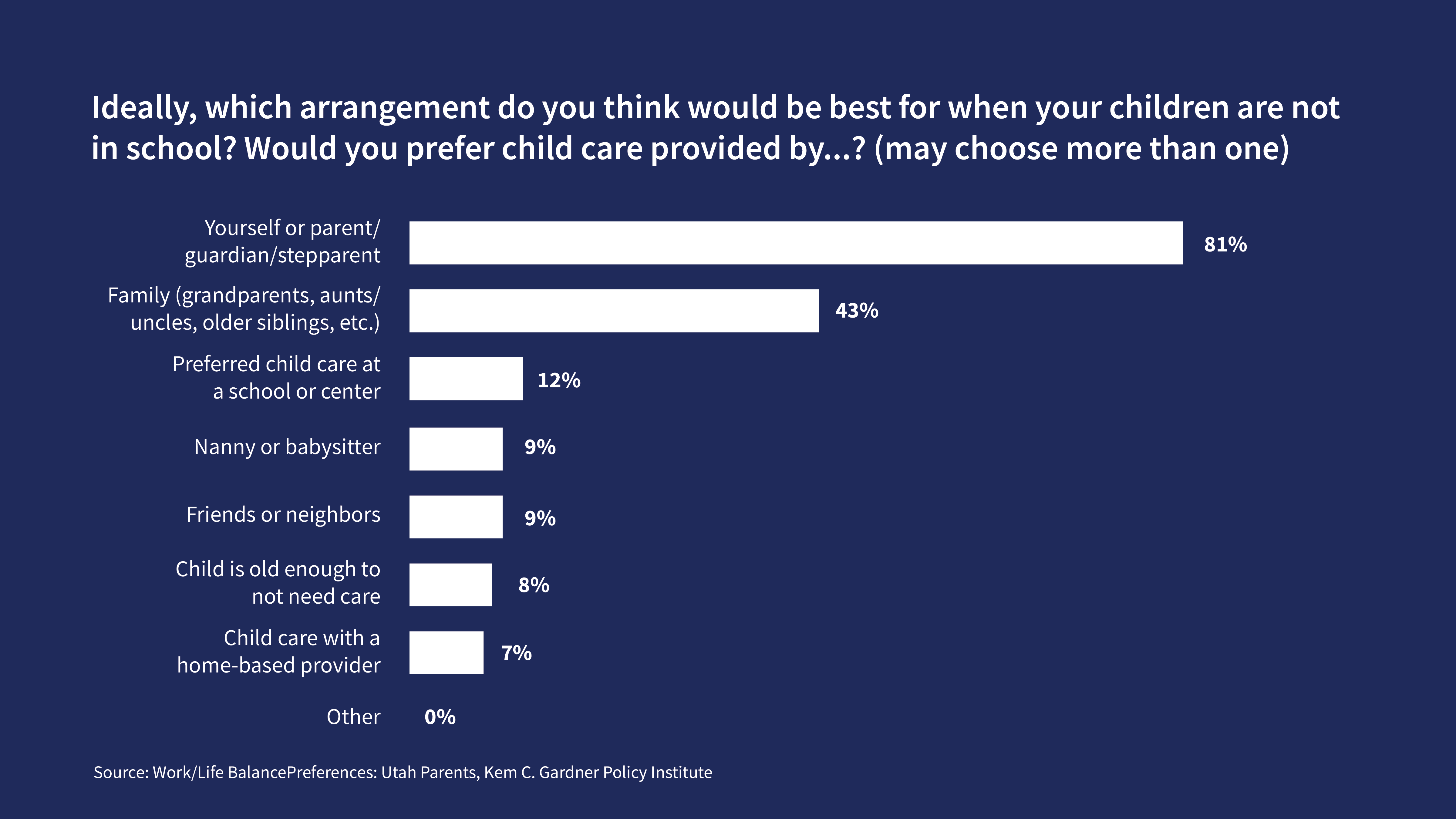

New research from the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute finds that 81% of Utah parents say having a parent or guardian caring for their kids outside school hours would be the best arrangement for their family.

The survey, “Work/Life Balance Preferences: Utah Parents” — commissioned by Utah Community Builders, the Salt Lake Chamber’s social impact foundation — examines what Utah parents think about work and child care. While the findings show ways to help make it easier for parents who want to work to do so, that’s just one aspect of family-friendly policy.

What parents prefer

While Shaha strongly supports child care options being available to those who need or want them, she and her husband were fortunate to find flexible jobs allowing one of them to always be with their kids. Many families want to move in that direction — but can’t.

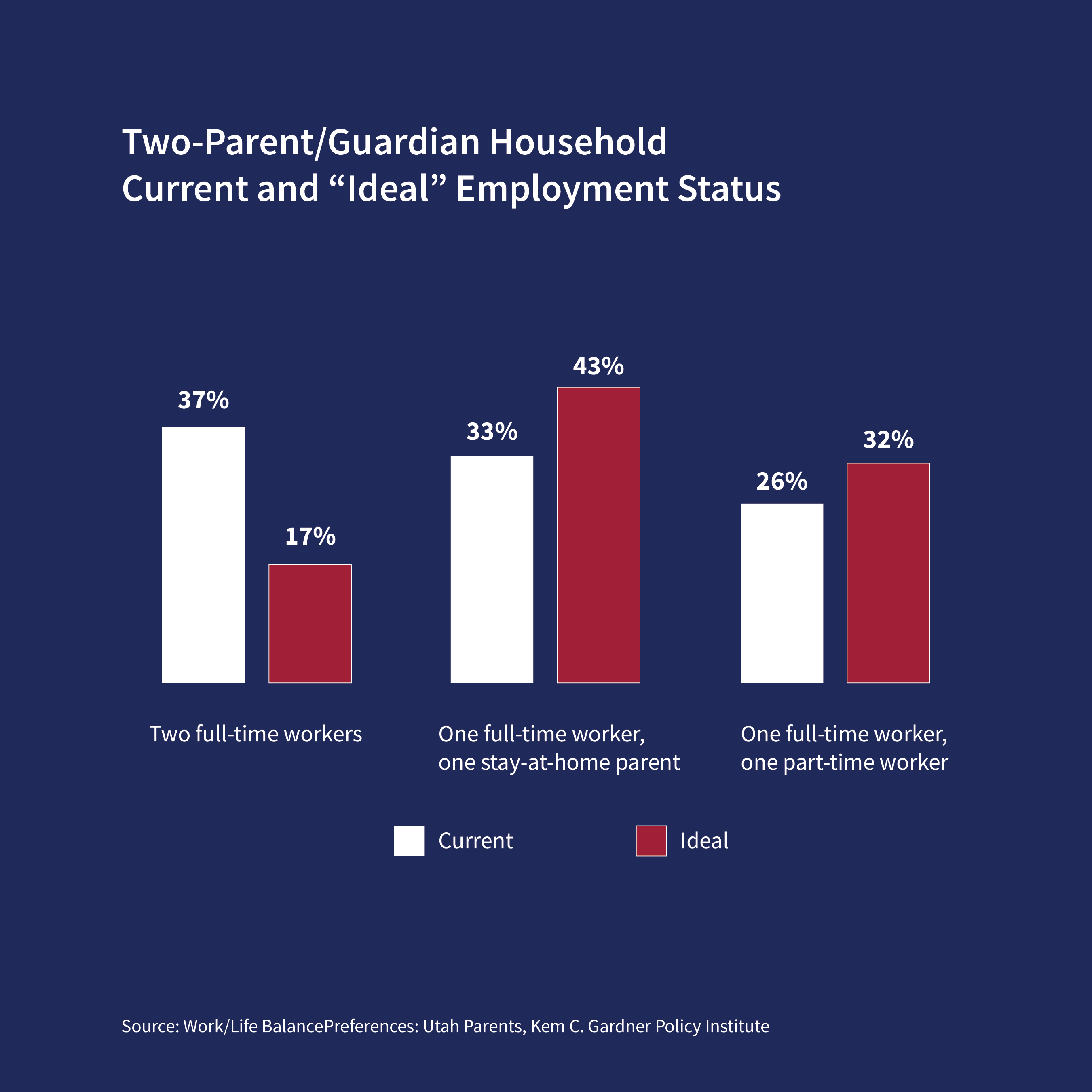

The Gardner survey showed that among two-parent households in Utah, 37% have two full-time workers, but only 17% report that as their preferred arrangement. Meanwhile, 33% have one full-time worker and one stay-at-home parent, short of the 43% saying that situation would be their ideal.

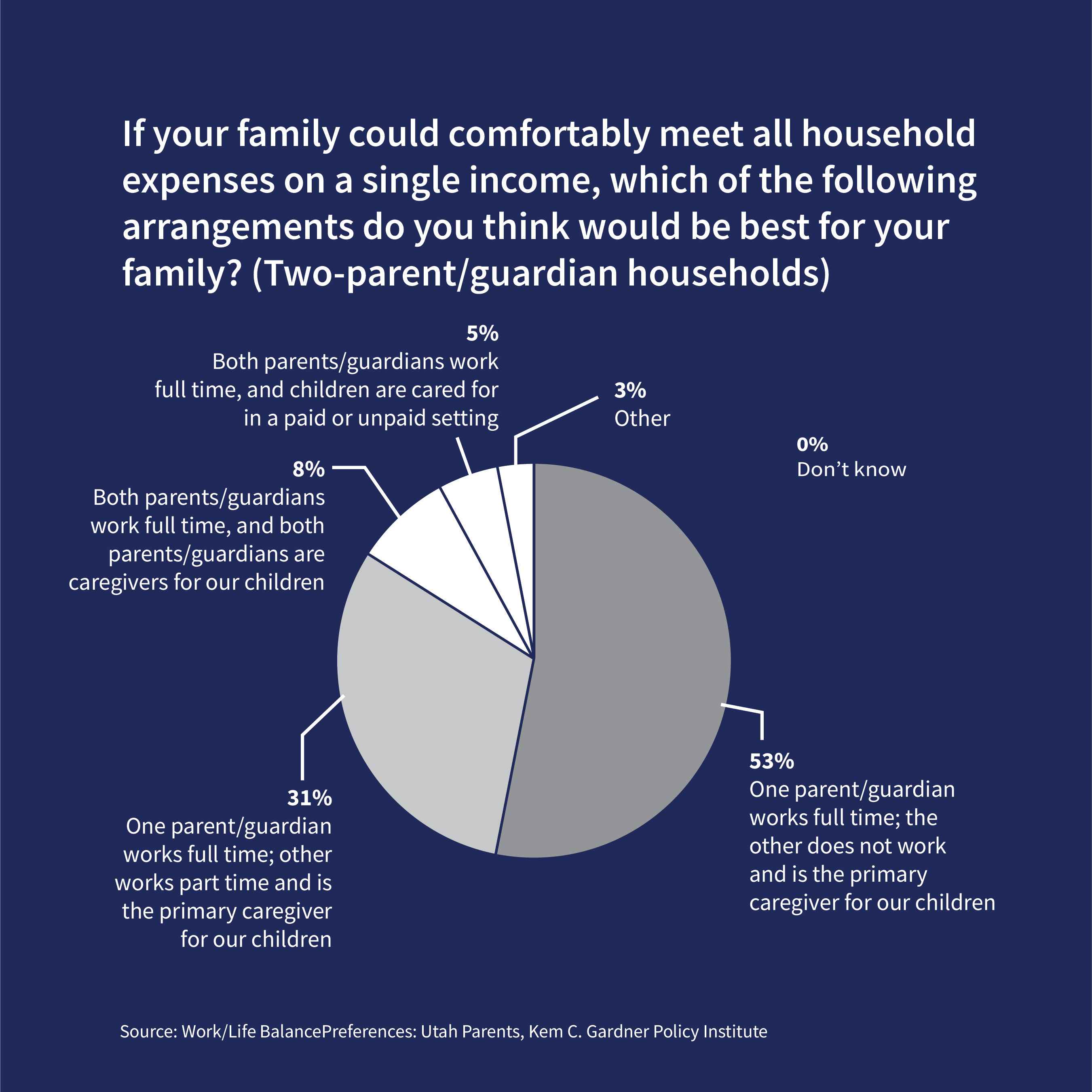

If they could make ends meet on a single income, most two-parent families in Utah would choose either one parent working full time and the other caring for children (53%), or one working full time while the other worked part time and still served as the primary caregiver (31%).

Utah isn’t an outlier in this.

“Homeward Bound: The Work-Family Reset in Post-Covid America,” a report from the Institute for Family Studies, co-sponsored by the Wheatley Institute, found that nationwide, a majority of mothers with children in the home preferred to work part time or not at all, rather than full time.

The 2021 Home Building Survey by American Compass found that “a full-time, stay-at-home parent is the most popular arrangement across lower-, working- and middle-class respondents.”

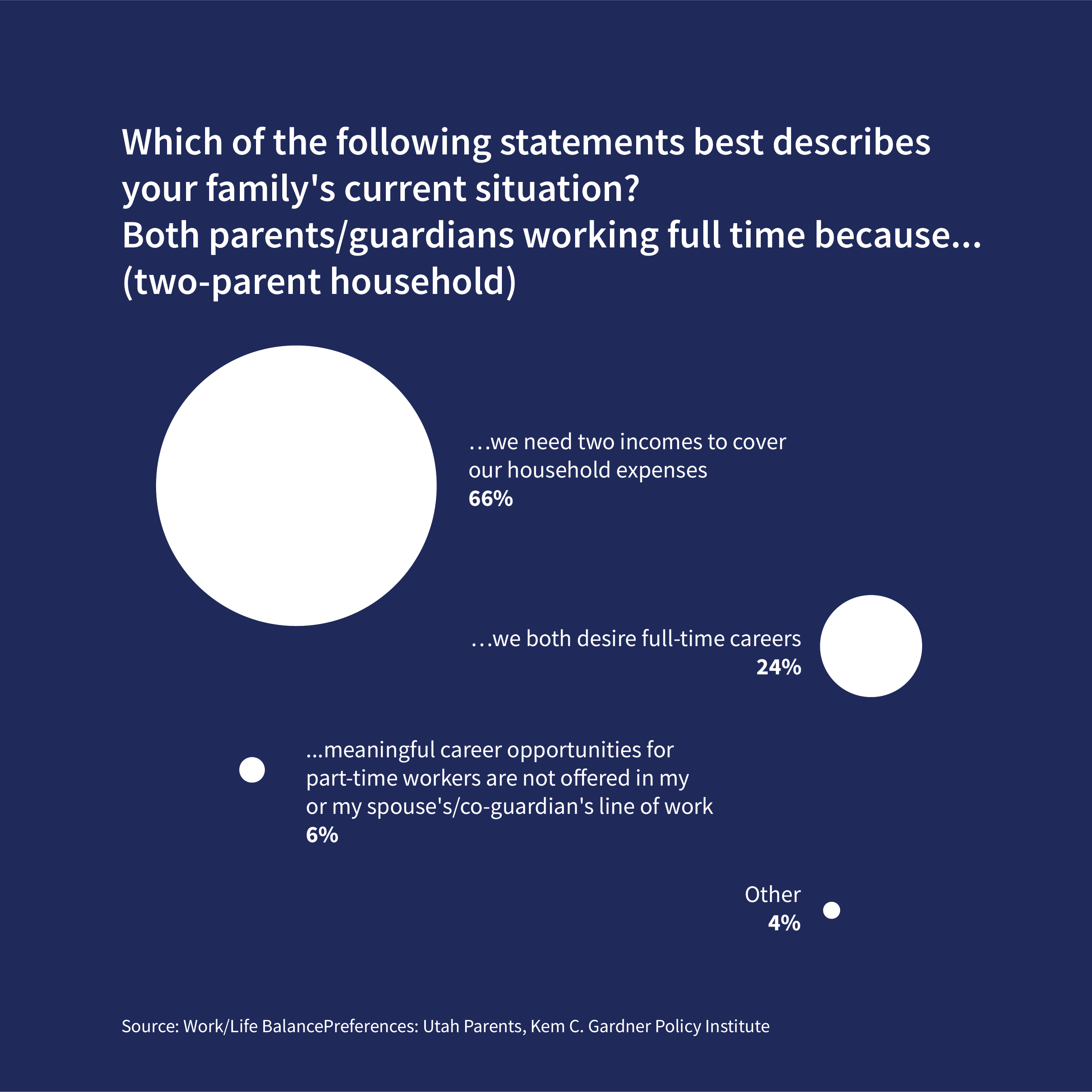

Advocates for assistance like child care subsidies rightly recognize that in most two-parent households in Utah (63%), both parents are employed, and many work full time. But among Utah families where both parents are employed full time, 66% said that’s because they simply need two incomes to cover household expenses.

That’s part of the reason why Amy Hunter and her husband both work full time.

“If we could financially match the level that we are at right now, one of us would be the caretaker for our children while they are home. It’s just not possible in today’s environment,” she said.

Flawed framing

The current rhetoric around family-friendly policies doesn’t reflect the unmet desire among many parents to create a work and family environment that allows more time with their children.

Consider how the White House’s 2021 American Families Plan framed the issue:

“Due to the lack of family-friendly policies, the United States has fallen behind its competitors in female labor force participation. … The high cost of child care continues to make it hard for parents — especially women — to work outside the home and provide for their families. … When a parent drops out of the workforce, reduces hours, or takes a lower-paying job early in their careers — even temporarily — there are lifetime consequences.”

Such framing is flawed.

Policies that attempt to be family-friendly solely by maximizing parents’ workforce participation are not in line with what most parents actually want. This narrow framing of family-friendly policy implies that parental time with children is a logistical barrier to strong workplaces, rather than an asset for strong families.

The current debate on both the state and national level is ripe for a redefining of what a truly family-friendly approach should be: to empower parents to create the care environment they feel is best for their kids, supported by the work situation that best supports their family needs and preferences.

Expanding the menu

None of this refutes the fact that many working parents — including single parents and those striving to escape poverty — absolutely need access to affordable child care in a safe and healthy environment. Nor does it diminish the vital work of child care providers, many of whom are still recovering from the effects of the pandemic. It also shouldn’t dissuade business leaders and policymakers from helping more parents enter and stay in the workforce.

It should, however, remind us that for many two-parent families, demand for child care services is often a symptom of the need for dual incomes simply to provide for a family.

When we view family policy through the lens of work, support for parents, such as access to child care, is important, but it should be supplemented by a broader menu of family-friendly workplace policies.

Some of the most popular workplace policies in the Gardner survey were things that give parents more autonomy over how they balance work with caring for their children: increased pay, paid family leave, flexible hours, predictable schedules and remote work.

Single-parent households on average ranked increased salary, better paying part-time jobs, and part-time job opportunities that allow career advancement as priorities.

“We’ve always been promised family-friendly work, but what we often try and create is work-friendly families,” said Richard Reeves, senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution, at a recent Wheatley Institute event.

Making work more family-friendly recognizes the importance of the family as a fundamental institution of civil society. But it also supports the workforce by better tailoring the many job opportunities in Utah and across the nation to the needs and preferences of parents. And it’s a smart move for employers who want talented employees who also desire a strong family life.

Working parents want to reprioritize time with their children. Given the long-term benefits of healthy families on educational, social and economic outcomes for children, they should be supported in this. And we can do this in a way that also supports workplaces.

Equipping parents with more freedom to realize the vision for work and family life that is best for them and their children will strengthen families, bolster our economy and respond to a crucial movement in American family life. Let’s not miss the opportunity.

More Insights

Read More

What you need to know about the upcoming state party conventions

The two major political parties are about to hold their state conventions. Here’s what you need to know.

Here’s why the First Amendment’s religion clauses are not in conflict

Some suggest there is a tension between protection for the free exercise of religion and the prohibition on the establishment of religion. But a better take is to see the two clauses as congruent.

Is California’s minimum wage hike a mistake?

Is raising the minimum wage a good tool to help low-income workers achieve upward mobility? That’s the key question at the heart of the debate over California’s new $20 an hour minimum wage law for fast food workers.