Written by Derek Monson

July 15, 2022

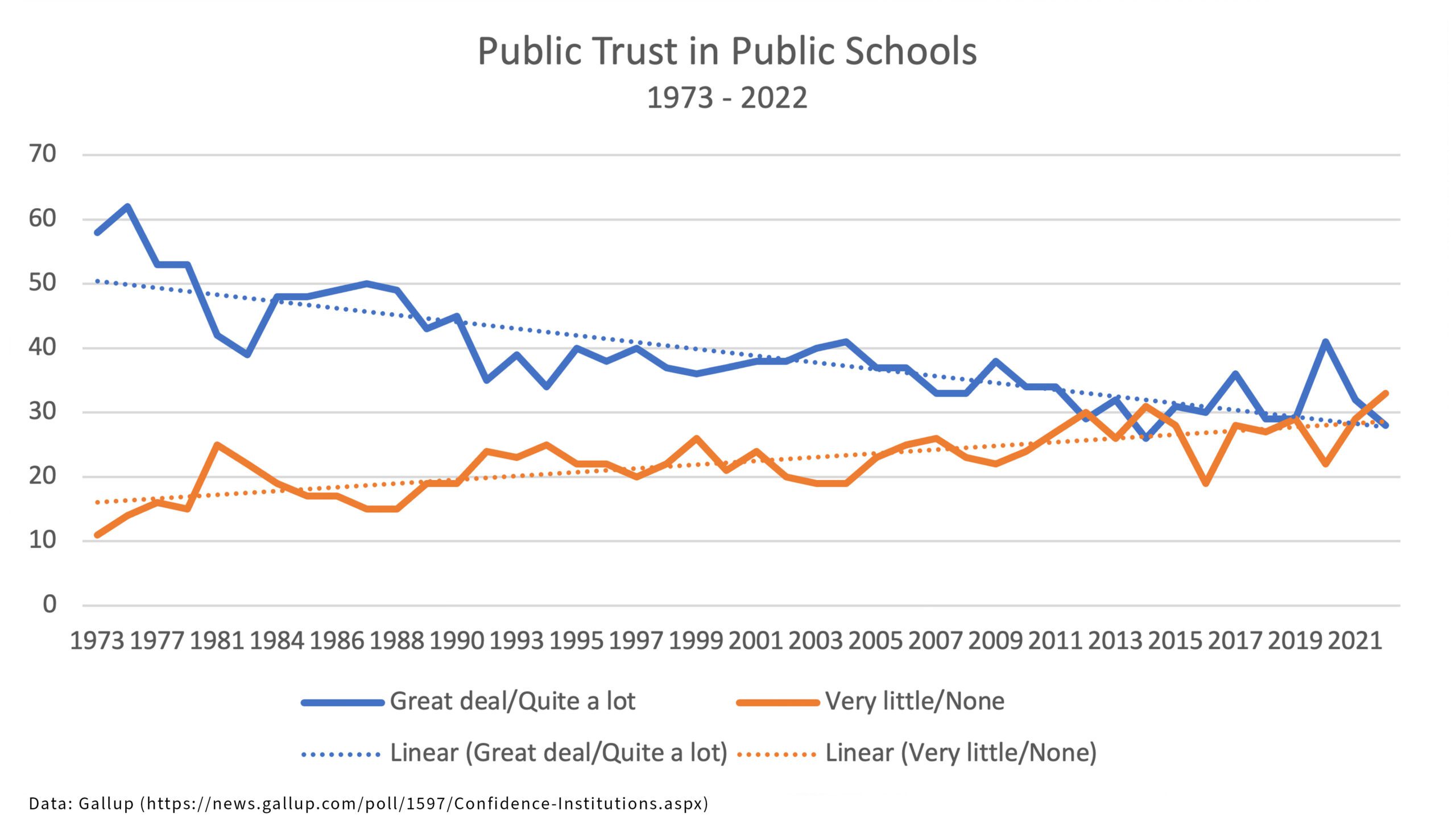

A recent Gallup poll reported that Americans’ trust in a variety of civic institutions has fallen to historically low levels. Results from that poll also offer some evidence that trust in K-12 public schools may be on track to become the next victim of partisan polarization. These trends should be concerning to every civic-minded Utahn and American.

Part of the solution to this problem is the restoration and reprioritization of the civic mission of public schools.

Tracking the problem

When you examine the Gallup data documenting the decline in public trust in public schools, an interesting correlation appears with the history of civics education in American K-12 public schools. In broad terms: As civics and history education have fallen down the priority list of subjects taught in public schools – deprioritizing the civic mission that was a primary purpose for creating a system of public education – public trust in public schools has declined.

The decline in public trust in public schools during the 1970s and early 1980s roughly correlates with the initial phase of the federal Title 1 education funding to help alleviate poverty and the creation of the federal Department of Education. A modest revival of public trust in public schools followed the 1983 publication of A Nation at Risk, which emphasized the reform of public education largely for national security reasons. That report, which examined the state of America’s public schools, argued:

Our nation is at risk. Our once unchallenged preeminence in commerce, industry, science, and technological innovation is being overtaken by competitors throughout the world. … If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war.

A further decline in public trust in public schools came in the late 1980s through much of the 1990s, as federal officials pushed for national education standards and holding schools accountable for the achievement of specific, measurable education outcomes. That push eventually led to the enactment of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) in 2002, which was in place until its repeal in 2015. Those years – another period of decline in public trust in public schools – was marked by a push for education reform driven by an economic focus on subjects important to employment and economic growth like math, science and language arts.

Public trust in public schools experienced a modest renaissance between 2014 and 2020. This period represented a shift in federal education policy away from trying to centralize education decisions in Washington, D.C. (e.g., national education standards, NCLB’s enforcement of nationwide school accountability standards through test scores). Instead, under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act which replaced NCLB, education decision making authority was pushed back toward state and local governments. This time period saw a growing interest in the idea that a main purpose of schools should be to make students “college and career ready.”

The decline in public trust in public education since 2020 has been a time defined by growing public education budgets and policy controversy due to the partisan politicization of education issues. Examples include critical race theory and social emotional learning in public school curriculum; a post-pandemic expansion of education choice programs; and identity politics altering the worldview of many traditional education advocates.

Hope for a solution

This historical perspective on the decline in both public trust in public education and American civic and history education is only broadly correlative. It does not prove a causal connection. But it does point toward some potential solutions that involve re-emphasizing the civic mission of public schools.

Survey research has found that both parents and teachers believe civics education ought to be prioritized on a level comparable to math and language arts. They also agree that their schools are not doing this. Restoring the civic mission of public schools – including establishing rigorous and sequential education standards in American history and civics through every year of the K-12 experience like those for math and language arts, increasing resources for schools and teachers for civics and history instruction, etc. – can help restore public trust in public education by reflecting the consensus between parents and teachers over what is most important in a child’s K-12 instruction.

Restoring the civic mission of public schools to its rightful place alongside academic and economic priorities is not a silver bullet for turning around declining public trust in public education. But given the broad consensus about its importance among parents and teachers, it is a good starting point. And in the process, we may just equip younger generations with the critical thinking and information consumption skills that they need to make the future less partisan and politicized – and more trusting in our civic institutions – than today.

More Insights

Read More

What you need to know about the upcoming state party conventions

The two major political parties are about to hold their state conventions. Here’s what you need to know.

Here’s why the First Amendment’s religion clauses are not in conflict

Some suggest there is a tension between protection for the free exercise of religion and the prohibition on the establishment of religion. But a better take is to see the two clauses as congruent.

Is California’s minimum wage hike a mistake?

Is raising the minimum wage a good tool to help low-income workers achieve upward mobility? That’s the key question at the heart of the debate over California’s new $20 an hour minimum wage law for fast food workers.